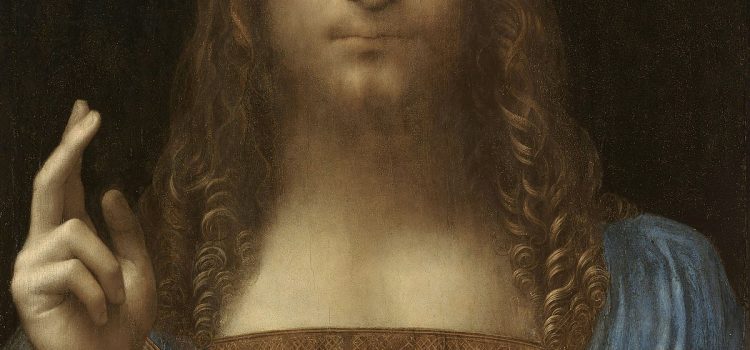

After restoration, it appeared to be a genuine work by Leonardo Da Vinci.

Yes, I believe it is. It was sold at Christie’s New York on 15 November for 450 million USD. The rediscovering of this painting has been a great story. It underwent a very strong cleaning, to remove all the additions made throughout the centuries but, after restoration, it appeared to be a genuine work by Leonardo Da Vinci.

This is proven also by several other clues: the pentimenti seen using X-rays, the brush strokes and the preparatory sketches found in his notebooks. This picture was possibly painted in Milan during his second stay and, perhaps for Charles D’Amboise, the French governor or even for his master, King Louis XII. Notwithstanding its grace, there is curious detail in this masterpiece which has been overlooked by historians and art critics: the cross on the orb is missing!

The representation of Christ’s as Salvator Mundi (Latin for saviour of the world) is not rare, starting with the end of the XV century: with Carlo Crivelli (1472); Cima da Conegliano (1497) and then several Northern painters, such as Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling.

Afterward also Leonardo Da Vinci, Durer, Antonello da Messina, Previtali, Titian and several others tried their hand at it, producing slightly different versions.

With such representation, Christ is always shown with the right hand raised in a blessing and his left hand is holding a crystal orb, surmounted by a cross, the ensemble is known as globus cruciger. Only in Leonardo Da Vinci’s representation of the Salvator Mundi there is no cross over the orb, which seems rather odd.

Given the fact that the orb put in the hand of Christ, not only represented the Earth but also the coming of the Apocalypse, it goes without saying that it is charged with deep eschatological meanings.

The use of crystal balls seems to have begun in Medieval times and some were found in the royal burials of the Merovingian.

The first documented use of a crystal ball to divine the future appears with the British mathematician and occultist, John Dee – an adviser of Queen Elisabeth I – who had claimed to have received it from an angel, on 21 November 1582 and then used it with fellow occultist Edward Kelley.

Kept with its mounting at the British Museum in London, it is made of beryl with a diameter of 6 cm.

Though its path is murky, the crystal ball was used throughout the medieval period by Anglo–Saxons as both a mean of magic and a flashy fashion accessory. It was suggested that Merlin chose to carry one, also made of beryl, in case King Arthur needed a quick prediction.

Since the cross over the ball is missing, is it perhaps a way for Leonardo to say that Christ was not the Savior but a wizard capable of playing tricks? It is well documented that Leonardo was an atheist throughout the course of his life, even if he did appear to have repented on his death bed, in Amboise, while giving up his soul in the arms of King Francis I of France.

It has been said that the orb does not show any distortion of light, but this may be due to the fact that Leonardo did not care much about it (perhaps made by one of his pupils) or that it is not glass by beryl. In a close up, impurities are highly visible inside the base of the ball.